- Home

- Wiersinga, Pim;

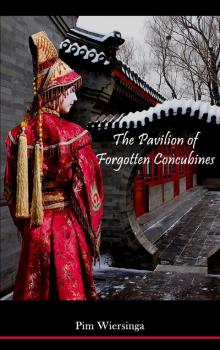

The Pavilion of Forgotten Concubines

The Pavilion of Forgotten Concubines Read online

Contents

Gentle Reader!

Part 1

Part II

Part III

Praise for: The Pavilion of Forgotten Concubines

In Dutch literature, China novels are scarce. ‘China’ features in Slauerhoff, D’haen, Schröder, and in Wiersinga’s debut Honeybirds. Now, Pim Wiersinga revisits China in a historical novel which has as its surprising starting-point The Dream of the Red Chamber, the great 18th-century classic by writer Cao Xueqin. The author introduces an imperial interpreter, Lady Cao, who once was the mistress of that writer and who is allegedly the model for the heroine in The Dream. The author is aware that such connections between real people and fictional characters intrigue Chinese readers

to this day, and the manner in which he connects the book

to society and politics is remarkably ‘Chinese’. More

‘western’ are the intercultural dimensions he adds: the

collision with the British Empire, as well as Cao’s romance

with Dutch envoy Isaac Titsingh.

—Marc Leenhouts, Sinologist, in Biblion

Not only does Wiersinga succeed in reviving a China of bygone days, he also masters the art of corresponding to perfection. Without realizing it, you read those letters as if they were addressed to you, taking courteous platitudes in your stride, like those who received them did back then. It’s all about what words disguise and reveal, and what is hidden

between lines. Treading on egg-shells, fearful tiptoeing, not wanting to disturb or harass; but say it nevertheless. The Pavilion of Forgotten Concubines is the kind of book the genre of the novel was made for.

—Ezra de Haan, poet and critic, in Literatuurplein

The protagonist, Lady Cao, wants to be with her lover,

the Dutch ambassador Isaac Titsingh. Yet when the

Emperor orders her to marry him, she refuses. I love the subtle power play, and the ever-shifting perspective. Wiersinga must have devoted a lot of thought to the form. It’s a clever construction. The letters bring out the web of relationships well, and the slightly archaic style is most appropriate.

—Alec Dabrowski, reviewer, Radio Rijnmond

The Pavilion of Forgotten Concubines

忘記妾館

Pim Wiersinga

Regal House Publishing

Copyright © 2017 by Pim Wiersinga

Based upon Het paviljoen van de vergeten concubines

Eerste uitgave (1st edition) 2014

In de Knipscheer

postbus 6107

2001 HC Haarlem

The Netherlands

ISBN -13: 978-9-0626585-4-1 NUR 301

Published by Regal House Publishing, LLC

Raleigh, NC 27612

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN -13 (paperback): 978-0-9912612-2-2

ISBN -13 (epub): 978-0-9912612-3-9

Interior design by Lafayette & Greene

Cover design by Lafayette & Greene

lafayetteandgreene.com

Cover photography by Valery Sidelnykov and

observe.co/Shutterstock

Regal House Publishing, LLC

https://regalhousepublishing.com

For Jaynie Royal

The author wishes to thank Ruth Feiertag, Jaynie Royal,

Marion Pellekooren, and Julie O’Yang for their

unstinting support.

To be surrounded by such muses is a privilege indeed.

Gentle Reader!

You are about to tread in the footsteps of envoys who sought to establish regular relations with China––which was a mysterious realm at the time in which these events unroll. Macartney, the first Western diplomat to strike a trade treaty with China in 1793, fails. This envoy is offended by the old Qianlong Emperor, the Son of Heaven, who may never be addressed by his personal name; all other rulers, including George III of England, are His vassals, obliged to kowtow in His presence. Macartney refuses to prostrate himself; he regards the ritual as an affront to the king he represents.

China’s prosperity starts to crumble, due to the massive extortions perpetrated by Grand Councillor Heshen, China’s corrupt strong man––as the next western envoy,Isaac Titsingh, perceives with more clarity in 1795. Titsingh is a seasoned official. A former regent of Deshima, the sole western trading post on the secluded isles of Japan, he was held in awe by the high and mighty there. Titsingh, who blithely kowtows in front of the Dragon Throne, is perhaps the most open-minded and philosophically inclined official Holland has ever known.

Rebellion is brewing among the Chinese populace. White Lotus, a band of women warriors, conspires to overthrow the Manchu (or Qing) Dynasty: the ruling family is rumoured to have lost the ‘Mandate of Heaven’, due to misrule. This spells civil war. Only the Censorate, a very powerful official body in China, may chide the Emperor or declare the Mandate forfeited. In refined circles, seditious sentiment takes on the form of ‘Ming-loyalism’––loyalty to the Ming Dynasty of yore (1368–1644), which legend and nostalgia have turned into another Golden Age. As late as 1913, adherents of Sun Yatsen will paint Restore the Ming! on Shanghai walls.

And in this novel, Ming-loyalism features as the key to cracking a literary mystery that has haunted scholars to this day…

I will no longer detain you, oh Reader. Follow me to the dungeons of the Forbidden City, where Imperial Interpreter Second Class Lady Cao suffers for the English Embassy’s breach of court ritual––instead of that Foreign Devil Macartney.

Pim Wiersinga, Rotterdam, April 2016

Part 1

Imperial Interpreter Second Class

帝國第二類解釋

Cao Baoqin

To the Son of Heaven, Forbidden City, Peking

May Your Majesty live ten thousand years! Do not lend Your ears to eunuchs who deem the slightest violation of protocol ill-omened: they are lusting after scandal. Indeed, the British ambassador did conduct himself scandalously, and I, the Imperial Interpreter Second Class, had to pay dearly for it. If I should lose my life in this dungeon, let the coroner mention two causes of death: hunger for paper and thirst for ink.

I make no complaints; Your Majesty’s Guards treat me well. Yet there are better ways to serve the Throne than by lingering in a palace dungeon! Alas! I cannot squeeze a decent proposal on the one scrap of paper allotted to Your humble servant. I hope I shall be granted, ere I part from All-Under-Heaven, writing implements to utter a request worthy of Your Majesty’s scrutiny.

Oh Son of Heaven, Exalted One! I am a relative of the late Cao Xueqin, the true author of Dream of the Red Chamber—a magnificent novel, written decades ago but only recently published in print. Without the reed-pen my spirit dies; when paperless, ideas wither. I am sure Your Majesty will understand: Are You not a poet Yourself?

Memorandum (no number)

The Qianlong Emperor

To his trusted confidant,

Grand Councillor Heshen

From Batavia, the main trading port of the Dutch in the Southern Archipelago, a request by the magistrate Ti Qing has reached Us: he desires to pay homage to the Dragon Throne on behalf of his country, in honour of Our Reign’s sixtieth anniversary.

Heshen! On several occasions you urged Us to refuse foreigners’ requests. We have not forgotten; We understand your concern. And yet Ti Qing has distinguished himself favourably from the common run of Red-Haired Devils. While chief of Deshima, the Dutch settlement in Nagasaki, he held China�

�s interests in high esteem and engaged in amiable relations with Our trading post there. Therefore We, the Emperor of the Qianlong era, shall benevolently welcome Ti Qing in the Forbidden City sometime next winter—provided this shan’t lead to one more infringement of the Rites!

The Dutch are to observe the kowtow, as all Our vassals do. Therefore you, my good Heshen, will ensure that they go through the motions of prostrating themselves before the Throne, foreheads touching the floor—as you should have done with that brutal Brit. Indeed it is you who merit punishment for Macartney’s refusal to bow down. The interpreter—Cao Baoqin We believe her name is—cannot be held responsible: she had been added to the British envoy because of her language skills alone. You are to release the interpreter forthwith and have her transferred to the Pavilion of Forgotten Concubines to await further notice.

Furthermore, We wish to know whether—and if so, to what degree—the Cao Baoqin woman belongs to the clan of the deceased Cao Xueqin who appears to have composed Dream of the Red Chamber thirty years ago. It is only recently, since its release in print, that his novel has acquired notoriety all over China. Is it true what has been whispered? Did Baoqin indeed engage in tender relations with the Dream’s late author?

To obtain intelligence thereof, you shall not subject her to one of your notorious interrogations. The Imperial Interpreter Second Class is a literate Lady; a decent supply of writing utensils will suffice to elicit confidences, and you will see to it that she receives reed-pens, ink-stone, and paper forthwith.

But before acquitting yourself of these tasks, rush to the trusted address and replenish the stock. Make haste, Heshen!

Pavilion of the Forgotten Concubines

Cao Baoqin, Imperial Interpreter Second Class,

to His Majesty the Qianlong Emperor

Deferentially Your servant addresses the Son of Heaven; she trembles with awe while prostrating herself in front of the Imperial Countenance. How is she to plead her case without causing displeasure? Without slighting the gratitude she owes His Majesty for release from a dungeon and for the refuge granted her amongst His forgotten concubines?

Barely beyond girlhood, I used to make author Cao Xueqin laugh when he—exasperated by comments of meddlesome relatives—despaired and even considered committing his life-work to the flames. Now, thirty years later, I wish to cheer You up, Oh Majesty, by confessing my gravest crime: I am perhaps the only woman in China who aspires to meld life-stories into a novel, following the illustrious example set by Dream of the Red Chamber, Cao Xueqin’s masterwork—yes, that is my crime!

What woman with a grain of sense beneath her skull would venture to embark on a masterpiece in prose? Had I excelled in strum ballads, ghost stories, or operas I should have acquired my share of fame; there would have been no need—provided I’m granted the favour—to submit my case to the Throne.

Misery began when I, Interpreter Second Class, was added to the envoy who refused to bow down to You—the bending of a knee, to which Macartney limited himself, was a deliberate affront. It will not have escaped Your Majesty’s notice that few of the Brits followed the chief envoy’s lead wholeheartedly; on young Staunton’s face, embarrassment battled with perplexity. I myself, who had to interpret the Brit’s intentions no less than his phrases, and who was not allowed to kowtow ere Macartney did so himself, well-nigh died for shame, even though I was spared the humiliation of having to render any verbal abuse: there was none. Macartney insulted the Throne without words.

Not all foreign devils are so ungracious. To atone for the brutal Brit, I would gladly offer my service when Dutch envoy Ti Qing is granted an audience—he is expected next winter, or so I am told.

Ti Qing and I have a long acquaintance, Your Majesty. Though his cradle stood in a swampy delta north of Franguo, he is—to the extent such a thing can be said of a foreign devil—a civilised man. In addition to his own language, he is in command of French, Portuguese, English, German, and Japanese: he speaks these tongues fluently. His Mandarin is less fluent, if truth be told, yet in virtue and nobility of spirit he sets an example to many a Peking Grandee! If it pleases the Throne to grant him a hearing, the encounter will remove the stain with which Macartney has soiled the Forbidden City and I would be honoured, Oh Son of Heaven, to mediate between the Dutchman and the Court! Discordances (solely conceivable because of Ti Qing’s poor command of the language) will be precluded through my agency; since my stay in Deshima I have mastered his tongue even better than English.

The Imperial Secretariat for Rites and Internal Affairs

To Cao Baoqin, Imperial Interpreter Second Class

Lady, do you truly expect the Court to discern in those scribblings of yours a serious request for release? Do you earnestly believe you qualify for such a rare honour?

You speak in riddles!

Your petition will not be considered, let alone presented to the Throne.

Pavilion of the Forgotten Concubines

Cao Baoqin, Imperial Interpreter Second Class,

to His Majesty the Emperor Qianlong.

Request for release

Oh Majesty! Your humble servant is truly indebted to You. Her plea for writing implements was met so promptly that she even considered resigning herself to her plight. What does one single life signify amidst untold millions? Were I seeking satisfaction for my sake alone, any request to be restored to former dignity would be but a speck of dust in the eye of a caravan merchant—irksome because its tiny size impedes removal. Nevertheless, I dare address You—out of concern.

We do not need anything from you—with these words Your Majesty turned down the British demand for trading

concessions in the Celestial Empire. And it is this response that troubles me night and day. We may need naught of the Brit, Oh Majesty, but it seems those Brits need many things—tea, silk, rice, rhubarb—and they desire to obtain these things from us. And the same applies for Ti Qing and his compatriots. Indeed, these red-haired foreign merchants may even be the salvation of China—of You!

Yet how can the silkworm pass judgment on the tree that gives it nourishment and life? Only the mulberry-breeder is entitled to judge. Whenever the mulberry tree yields cocoons of poor quality or naught at all, the breeder prunes it back; when the tree yields plenty, he will plant more trees. In short, the silk grower knows what he is doing—even if his assistants’ zeal exceeds their intelligence. If heeded, his helpers’ loud-mouthed counsel cause the breeder of silken threads to lose the Way—his ears whizz, eyes cloud, mind becomes bedazzled with words that, no matter how pleasing to the ear or plausible to the mind, flatly contradict themselves. Thus it may come to pass—it is out of concern that I dare speak!—that His Majesty, despite the ten thousand years His subjects wish for Him, may lack the time required to detect each and every inaccuracy in the endless memoranda submitted to the Throne.

Your Majesty! A silkworm cannot judge silk. Likewise I am entitled neither to endorse nor to reject the Imperial Will. Your wisdom is proverbial. Nothing pleases Heaven more than Your Majesty’s desire to protect helpless subjects against pirates and foreign intruders. Nevertheless, China would benefit from industry, commerce, and traffic. Our densely populated Empire thrives on exports, imports, and busy harbours; caravan routes overland no longer suffice. Wisdom tells us to honour the ancestors, to follow the Ancients and to propitiate Heaven—as well as to think ahead. Someone must offer up the mirror, Oh Majesty, and if Your salaried Councillors fail to do so, let it be me, come what may! If only virtuous peasants, artisans, and merchants, despised by Peking literati, were encouraged in their endeavours instead of being scorned and extorted, I daresay they could meet the needs of the entire world. Look at Japan! Of course our Celestial Empire by far surpasses that sealed-off island in refinement and civilisation, yet one must concede that the Shogun, with a Chinese colony and Dutch tra

ding post at Deshima, found a most favourable harmony betwixt protection of his worthless isles and participation in overseas trade.

I am sure such issues have deprived Your Majesty of sleep for years, so I shall not dwell on them unduly and

will limit myself to the observation that many a courtier

in the Forbidden City—especially those who prefer to call it ‘The Great Within’—darkens Your glorious reign with mindless aversion to all things foreign. They merely strive to fill their rice bowls the way their forbears did—or rather, to have official rice bowls filled by the labour and toil of peasants. Do courtiers ever devote one thought of gratitude to the poverty-stricken millions?

You do, Oh Majesty! You are like a father to all. How often have You waived taxation on the neediest of subjects! Your benevolent intervention rescued many a life. Your Majesty’s compassion merits praise and proves You wield the power to change All-Under-Heaven for the better! Having said this, I must add that too many interventions, however, weaken Imperial prestige. Any waiver sows doubt as to the fairness of the tribute. If China is to flourish, the Court must find a way to collect taxes in a consistent and just manner.

Earthquakes are preceded by the subtlest of subterraneous rumblings. These will pass unnoticed, until ramparts and walls deemed impregnable start to show tiny cracks. Likewise, keen observers have noticed the first signs of China’s decay, its prosperity notwithstanding. The poverty of peasants is such a sign,Oh Son of Heaven! The real peril resides not in foreign devils but in earthquakes caused by a populace being now overtaxed, then exempted. As long as cultivators of soybeans, rice, and kaoliang remain famished, their bowls scarce of grain, and their offspring in a state of near-starvation, the entire Empire suffers from famine. If only their masters would enhance affluence through sound investments in the land’s fertility instead of squandering silver on Peking belles, and if only agricultural zeal were augmented by Peking support—then our peasantry could easily provide villages, towns, and regions, indeed vassal states in far parts of the world, with rice and riches, and fill their own bowls—much as Your porcelain factories bedeck the world with beauty!

The Pavilion of Forgotten Concubines

The Pavilion of Forgotten Concubines